Sustainability: Design For Longevity

In a culture that is so frequently obsessed with new, how can we design objects and spaces that lend themselves to longevity in both the physical and psychological realm?

Eternally Yours: Time In Design calls this the “psychological lifespan” of our physical surroundings. This is an important topic in the realm of design, and one not often at the forefront of sustainability when it comes to the lifecycle of the materials we use.

While we often use LCA (Life Cycle Analysis) to assess the environmental impact of materials throughout their lifespan, we rarely consider the broader cultural setting in which it is surrounded. As the authors say in The Things That Matter, “LCA allows us to design products that are friendlier to the environment, but leaves a fundamental problem unaddressed: the short lifespan of our surroundings. We live in a throwaway culture”. [1]

“LCA allows us to design products that are friendlier to the environment, but leaves a fundamental problem unaddressed: the short lifespan of our surroundings. We live in a throwaway culture”

THE THINGS THAT MATTER, PG.28

If we begin to understand the psychological lifespan as being a key piece to the sustainability puzzle, our role as designers is to design experiences, space, objects and interactions that work toward longevity. We work on understanding our users and what emotive value we can bring to their lives through our design that will encourage long-term engagement. This relationship continues in how our clients build lasting relationships with their own spaces and communities after we have completed the design phase. The focus should be on maintaining relationships with their community rather than selling products to customers—if these relationships have a durable character, so will the products and spaces. [2]

Here are a few ways we can address these issues and get our users, their motivations, thoughts and hands involved in the process:

1. Designing Spaces that Bring People Together and Have a Lasting Quality

As we begin to see technology replacing physical objects in our lives it begs the question of where the role of design for physical interaction is headed. An exciting part of our role as designers is the connection we can create between an artefact in the physical realm and how that brings people together. As retail interior designers, we create spaces that aim to have a lasting and successful impact on the businesses we work with, as well as the surrounding communities.

Part of what we do best is design research at the beginning phase of our projects and all throughout the design phase. We work to understand our clients needs not just for today or tomorrow but to create objects and spaces that are timeless and will function long term. This involves looking at the past and looking to the future to come up with the simplest and most effective solution. Sometimes the most pared down design is the most effective. We seek to move away from trends and short term desires and move towards solutions to real problems that affect the way people move and feel.

Muji’s Simplicity & Timelessness

We recently heard the Chairman and Representative Director of Muji speak of their philosophy to create objects of value, using a rigorous process of subtraction in their design. Their ‘brand’ is built on the basis of an anti-brand mentality that rejects trends in design and fashion and seeks to create timelessness in simplicity.

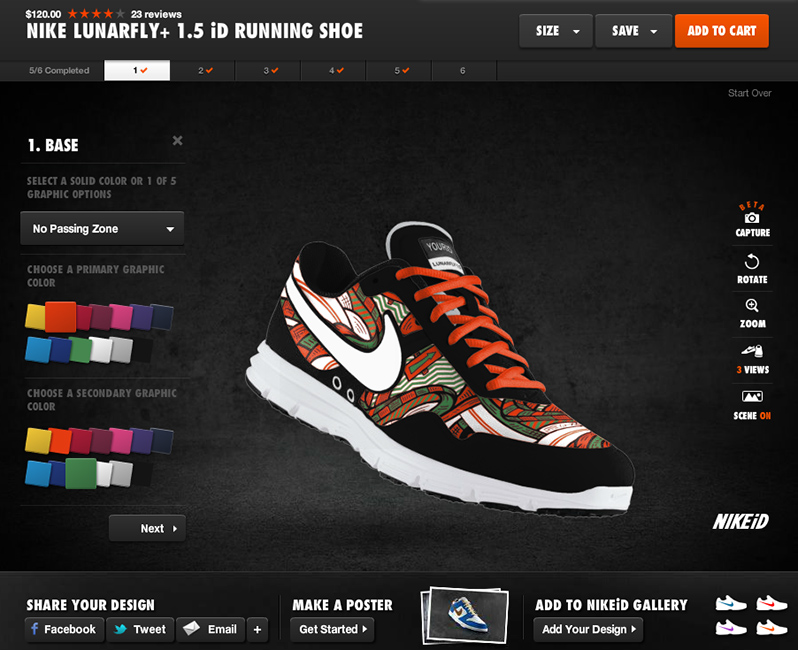

2. Personalization in Design

As the needs of our communities change over time, we want the spaces we surround ourselves in to change too. We want to design the ability for this to happen organically and design key ways in which our clients can have their spaces reflect their brand as it grows. Designing systems and spaces that our clients can personalize is key to the longevity of the design. It’s what allows people to feel an emotional connection to the objects and spaces around them.

NikeID’s Personalized Sneaker Design

A good example of a system that uses design to create a personalized connection between the product and its users is NikeID. Users come up with their own version of their favorite Nike shoe, it tells a personalized story that runs deeper in the user’s mind and creates a lasting connection with the object. Good personalization is invisible, it is not perceived as a special effect or something exceptional but smoothly accompanies its users expectations and needs. [3]

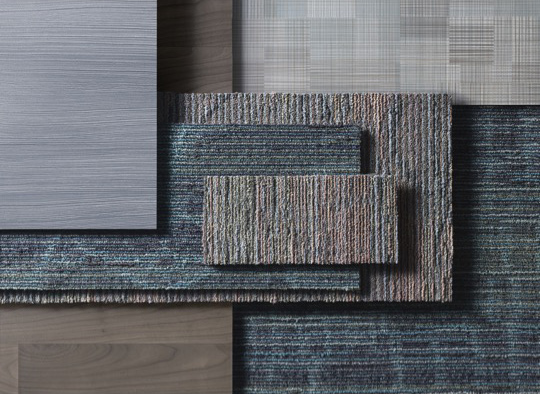

3. Designing For Wear and Repair

Designing with (and within) systems that can easily be repaired is an important part of designing for longevity. Many interesting open source concepts are popping up to support the idea that self repair is achievable through shared knowledge networks.

Modular Flooring by Interface & Mohawk Group

Flooring is one example of where companies are using systems thinking to design products where individual panels can easily be repaired or replaced without needing to rip up the entire flooring. Companies like Interface and Mohawk Group are coming up with modular flooring solutions that allow flooring to be selectively repaired or replaced as they wear on a large scale.

Conclusion

Within a culture of rapidly changing tastes and trends, our role as designers is to create objects and experiences of value that create lasting relationships between our clients and their users. As designers, we are working within the realm of creating and shaping our physical environment. It is our role to consider how this physical environment we are working to create has a lasting effect on the environment. A huge part of this involves designing for psychological longevity. That is, using systems of repair, replacement, and personalization to shape and contend with the way people feel within a constructed environment. All of which can be achieved through a deeper understanding our clients and users needs, as well as a conscious turn toward designing for the type of physical interaction that will allow users to build a lasting relationship with their surroundings.

References and Sources

2. The Things That Matter, p. 30

3. Material Encounters with Digital Cultural Heritage